Cycling the Lower Omo Valley to Omorate and on to West Turkana

We would have loved to stay in Addis Ababa for Christmas. But, alas, we had to race to Kenya before our visas expired on the 31st December.

From Addis Ababa, the conventional route to Kenya is the road directly south towards Moyale. However, the first few hundred kilometers of the road in Northern Kenya is renowned for bandits and we’d therefore either have to take transport or an unnecessary risk.

Another option was to head southwest from Addis into the remote tribal lands of Ethiopia before crossing the border at the northwest of Lake Turkana in a no-mans-land between Ethiopia, Kenya and South Sudan. This route isn’t without its dangers though. But, for the touring cyclist, it offers the chance to see various tribes up close and to visit one of the remotest parts of Africa. We decided to give it a go.

Once we escaped the traffic on the road out of Addis, we had a straightforward 80km to Kela on decent road. Except, that is, for the reemergence of the children who, at each and every opportunity shouted the country-wide catchphrase of youyouyouyouyouyouy…moneymoneymoneymoney…penpenpenpenpen whilst running after us. Rocks were thrown.

At Kela, we checked into a grotty ‘hotel’ in the centre of town. We couldn’t blame them for not having running water or a reliable power supply. But we both took exception to the turd we found in the sink of our en-suite ‘bathroom’. Luckily for the boy I made to clean it up, it wasn’t a fresh one so he was able to chip away at it until it came off the basin.

The next morning we passed through Butajira and were astonished to find a plush western-style hotel. We stopped for a cup of tea in the marble-clad restaurant and decided that, as it was Christmas day, we would find somewhere nice to stay that evening where, hopefully, there wouldn’t be any poos in the basin to greet us.

We aimed towards Hosaina where we had been promised a decent hotel and since it was Christmas Day we were extra motivated to reward ourselves with a cold beer and a pizza.

Further down the road, we looked in dismay at our intended turnoff towards Hosaina because the road was nothing but a stretch of rubble. We opted to continue on the tar road but this meant a longer cycle without knowing what the elevation was going to be like.

We didn’t think the road would be too hilly, but we were taken by surprise.

We spent 10 hours in the saddle on Christmas day. We covered 145km and ascended over 1,600 meters. All to the constant and irritating accompaniment of youyouyouyouyouyouyouyouyouyouyouyouyou, moneymoneymoneymoneymoneymoneymoneymoneymoneymoneymoneymoney and rocks thrown at us regularly. All Emily could think about all day was her new-found dislike for Bob Geldof as she spent the entire day singing “Do they know it’s Christmas?” and, perhaps unjustifiably, blaming him for the rock throwing child beggars.

Utterly exhausted, we eventually got to Hosaina and limped into the first western-looking hotel we could find. We stumped up an extortionate (550 Birr/£17 for the night compared to our usual 100Birr/£3.00 per night). But, it was Christmas and we thought we’d give ourselves a treat. The 566% increase in cost did not equate to a similar increase in service though. Although we enjoyed cool beers, a pizza and a comfy bed, we had to endure the sound of the very loud Christian Orthodox church across the road wailing all night and, at 3am, I woke the pigeon that had been sleeping in the bathroom and spent 15 minutes trying to catch it as it flapped around the room.

We had a similarly tough ride the next day to Sodo. We saw the first troop of baboons of the trip cross the road ahead of us but the day’s ride itself was made worse by the children and villagers.

As we approached each village, high-pitched screams of “Farange!” would greet us from the sidelines. These shouts rippled up the road before us until the whole village knew to expect us so they could each run out to shout youyouyou, moneymoneymoney, penpenpen and “where-you-go?” at us. With such an early warning system in place, it’s little surprise that Musolini failed to colonise Ethiopia.

At one of the larger villages, we pulled over to the side of the road and, before we could even park our bikes, people had surrounded us. By the time Em returned with two warm bottles of the fizzy stuff, she could barely find me amongst the throng of kids and adults standing, staring, playing with the bikes and asking for money.

Just before we reached Arba Minch, we met Jimmy, a French motorcyclist who was making the long journey from Cape Town to France. He recommended the Bekele Mola hotel to us so we headed there. In their reception they have a sign proudly stating that Ethiopians pay 400Birr and Foreigners pay 580Birr for a room. Camping in the grounds was 300Birr. Needless to say, we weren’t happy with the price differential so negotiated to pay the Ethiopian rate for a room. Which was lucky because warthog roamed the grounds we could have camped in. The view from the hotel’s terrace across the two lakes was stunning and more than made up for the overpriced room and food.

A couple of hilly days’ ride through banana plantations later we made it to Konso. We couldn’t find any decent places to stay in town so we climbed up a massive 20% hill where we’d seen a lodge marked on the GPS. With panoramic views over the countryside (a UNESCO heritage site due to the uniqueness of the hill terraces) and an expensive-looking restaurant, I thought the receptionist had made a mistake when she said it was “55 for the night”. That is, until I realised it was US$55. At that price, we had to find somewhere else to stay…which meant travelling back down the hill we’d just cycled. Thankfully, the lodge agreed to store our bags and bikes and we got a tuktuk into town.

There, we found a much cheaper hotel where I negotiated the price down from 200Birr to 50Birr for the room on the condition we buy a few drinks. We had couple of beers, paid the 50birr for the room and headed into town for some food.

At the restaurant, ordering our meal was tricky. Firstly, as is common with most Ethiopian restaurants and hotels, the TV is on at full volume meaning nobody can hear anything other than the din from blown speakers.

Secondly there’s a bizarre phenomenon that’s quite unique to Ethiopia. When taking an order for food or drink, the waiter will turn on his heels after the very first item you say. It’s happened at nearly every place we’ve eaten. For example, if you wanted one spaghetti and one pizza, you’d barely be able to finish saying “one spaghetti” before he’s off to the kitchen…even though there’s at least one more dish and a couple of drinks to order.

Thirdly, it was another occasion where the waiter insists that there’s only one thing on the menu. We reluctantly order it. Later, whilst we’re eating, other diners who’ve arrived after us are brought much more appetising dishes. When we inquire, the waiter will say that’s available too. When we try to order it, they say it’s run out. I only mention this because it’s happened several times in Ethiopia!

Anyway, we had a reasonable meal and had fun meeting Harley and Emily, a couple travelling from South Africa to Sweden in their Land Rover.

Back at the hotel we were preparing for bed when there was a knock at the door. Apparently the room was now 150Birr and not the 50Birr plus beers I’d agreed. After a long ‘conversation’ I was forced to stump up the 150Birr for the privilege of the grimy room with the sound of yet another TV turned up to number 11 in the courtyard outside our room.

The next morning we took a tuktuk back up the monster hill to collect our kit and bikes. At the lodge, we met Tom and Eva, a South African couple who are travelling Africa in their huge unimog 4X4.

The cycle out of Konso was beautiful but hilly. Every inch of the surrounding hillsides was being used for agriculture in an intricate pattern of interweaving hill terraces.

Then something expensive happened.

I swooped down a lovely decent towards a bridge that crossed a partially dried-out river. What I failed to notice until it was too late was a 15cm ‘step’ right across the width of the road where the bridge joined the tarmac road.

I tried to bunny hop, but with a combined bike and rider weight of over 150kg, I could just lift the front wheel enough for it not to take the full force of the collision. The impact was hard. And a sickening crunch rose up through the wheels, into the frame and into my bones as I collided with the obstacle. I just managed to keep control of the bike and avoided a crash but I was helpless to stop my handlebar bag fly open and all I could do was cling on as I watched my beloved Nikon DSLR camera and various other bits of tech hit the asphalt with an expensive smash.

To their credit the kids hanging around the bridge quickly gathered up all the broken parts and handed them back to me. The camera was dead. I was gutted because of the remote and photogenic region we were to cycle into. But, with no obvious signs of damage to the bike and no injuries, the journey continued.

A short while later, Tom and Eva passed and handed us ice-cold waters from their huge vehicle. After the hot water we’d been sipping from our bottles all week, the crisp coolness of fresh icy water was like sipping vintage champagne.

Tom said they were headed to a campsite 75km away. It was 1pm and 75km in an afternoon is quite punchy for anyway but, with Tom’s promise that a cold beer would be waiting for us, we decided to give it a go.

At Woyto, there’s a junction. The asphalt road continues on a longer, potentially hillier road towards Omorate. The turning left is on a hard-packed rough road but it’s shorter. We met Christian, a missionary form Iceland who was visiting friends in the area. He advised that the shorter but unsealed road was best for us. We took his advice and I lead the pace on what Emily called “James’s Omo Valley Training Camp”. Tom’s ice-cold beer was a big carrot dangling in front of me!

Our chosen road took us across the Lake Stephanie Nature Reserve. Lake Stephanie is dry pan but recent rains had caused an explosion of green in the otherwise arid landscape. Butterflies danced beside roadside ditchwater and crickets played a game with us by jumping ahead – always managing to keep at least a meter ahead of our wheels.

The road was rough and there was no way we could make Tom’s campsite. Instead, we stopped at Abore, a tribal village where hundreds of well-behaved kids came out to greet us. A friendly chap called Simon lead us to the water pump where we filled up and then to a small bar where we bought him a Coke and met another guy who was a guide from Konso. He invited us to camp with him in the bush that night.

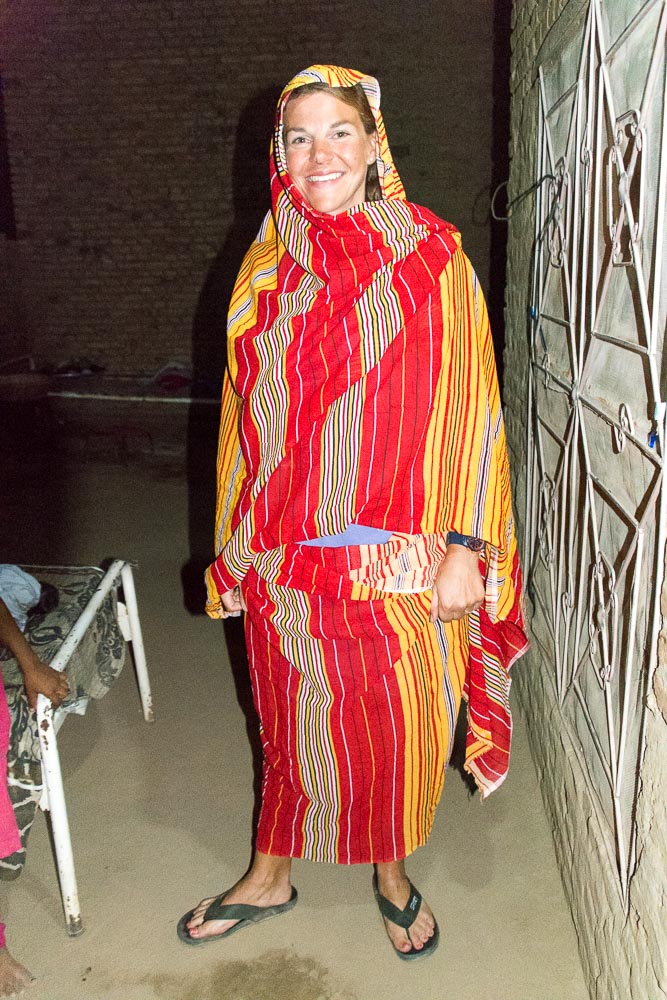

We pitched our tent amongst several straw huts and chatted to some of the tribe who lived there. The women wore hundreds of stacked neck beads and the little children had painted white faces. They were all very friendly and accepting of our intrusion into their normal life and not a Birr was asked for. We drifted off to sleep to the sounds of traditional singing floating across the bush from a nearby camp knowing that this was a true African experience that we were incredibly lucky to have.

We’d established from the guide that Tom’s “75km to the campsite from the turning” was somewhat inaccurate. In fact, it was 75km from the village in which we were camped. We set off early to get there.

The road conditions were awful for cycling. There were countless dried up creeks that crossed the road so we couldn’t get any rhythm going and had to keep dismounting to push through the sand. Progress was slow and exhausting.

In the afternoon, we had 30km more to travel but the road disappeared altogether. Instead, we had to haul our heavy bikes through the sand of a dried-up riverbed and then up a 15% track that was nothing but loose sand and rubble. At times the road was so steep that we had to push one bike together up the hill and then return for the other, as it was too steep to push alone. How we regretted not taking the asphalt road and kept remembering the words of the Icelandic missionary who categorically said to us, “It’s not that bad at all, there is a small hill but you should be fine.”

For 8 hours we didn’t pass a single village. There were very few people. Of those we did see, some ran off into the bushes upon spotting us. Those more inquisitive folk would return our waves. All the males had little hand-carved stools which they carried everywhere with them. The tribal people seemed more mild-mannered and for us, seeing rifles harmlessly slung over shoulders rather than fast approaching rocks was a relief.

We were exhausted and dehydrated having pushed up over 1,200 meters of ascent through sand and rocks. At 4pm, we saw the first vehicle of the day. They stopped and, when they told us where they were going, we simply could not refuse their offer of a lift.

We joined Rokhan, who was on holiday from Sri Lanka, his guide and driver for a 10km drive deep into the bush where we witnessed one of the oldest and most bizarre tribal ceremonies. The Jumping of the Bulls.

The woman couldn’t have been older than 25. She blew her horn. The man facing her raised his whip and with almighty force thrashed it across the woman’s bare back. The whip tore into her skin. The woman bowed towards the man. Again and again this happened. Each time, the woman would take a single hard lash across the back. It must have been agony. But she barely flinched.

We learnt that, as part of the ceremony, the women beg to be whipped as a sign of their love for the man. It might be the male’s mother, sister or niece taking that takes the beating.

The women of the tribe then stand in a circle, backs towards us. We saw blood dripping from the open wounds. Flies landed, looking for somewhere to lay eggs. The scars of previous whippings were evident.

We were on to the main event.

Several bulls had been let into the field. About 8 bulls had been pushed, prodded, yanked and twisted so that they were now standing in a line. A naked man edged backwards, eyeing up the task ahead. His challenge was to leap up and run across the backs up the bulls without falling into the gaps between. If he succeeds, it marks his passing from boy to man.

He took a run up and jumped up to the first bull that reeled from the impact of the chap’s foot on its flank. He then skipped across the moving obstacles before losing his footing just short of the final bull. He repeated this 6 times. Everyone cheered and he was adorned with a garment for his neck. He was now a man…and so started 2 days of celebrations.

It was now sunset. Rokhan’s driver dropped us off the short distance to our campsite near Turmi where we finally met up with Tom and Eva at their Unimog. They cooked us a delicious pasta meal and we thoroughly enjoyed their company…and that ice-cold beer that we had suffered so much for.

It was a relief that the 50km from Turmi to the final town in Ethiopia, Omorate was a gentle cycle on beautiful smooth tarmac. We headed to the immigration office where we had to guide the official, who was clearly drunk, through the process of stamping our passport with an exit stamp with the next day’s date. The process took a while because he couldn’t get his fuzzy head round the concept of our visa being valid from the ‘date of entry’ rather than the ‘date of issue’ which he was insisting was the case. He claimed we were in the country illegally and threatened to take us to Addis Ababa. We were there for over an hour before his desire to return to the bar took over and he finally stamped our passport.

Omorate doesn’t have anything to offer. Not even electricity. And we even struggled to stock up on food for our journey into Kenya. But we did manage to get a friendly chap to charge our Goal Zero Sherpa 100 power pack so we could ensure our GPS would work for the journey ahead.

We’d heard many tales from other travellers that crossing the bridge over the Omo river is an issue. Policeman guard it and insist that it’s closed, despite locals walking across it, forcing travellers to pay for a boat or dug out canoe across the river.

When we approached the bridge, we could see the police guards and, from the distance, they were waving us back. We continued and, just as we approached them, a big pickup truck thundered up on to the bridge from the opposite bank crossed over and passed us. There was no way the police could claim that the bridge was closed now. They made a cursory check of our passports and to our relief, we cycled over the bridge.

Once we were on the far bank, our challenge was to negotiate a confusing network of sandy tracks towards the Ethiopian army checkpoint then through the arid no-mans-land before getting to the Kenya border checkpoint.

This was hot, dry and the sandy conditions of the road made cycling impossible. The weight of our bikes, now even heavier with the weight of 10 litres of water each and food supplies for up to one week, cut straight through into the sand causing a few low-speed crashes.

We had to haul our bikes through the sand. It took us 4 hours to make the 29 kilometers from Omorate to the Ethiopian army checkpoint. The friendly squaddies offered us water and we relished the shade. But we had to press on.

It took us a further 2 and a half hours to haul our bikes through the sand over the 7km between the Ethiopian and Kenyan border checkpoints. We arrived exhausted.

The Kenyan policeman took our details down in a book (we couldn’t get our passport stamped because it’s not an ‘official’ crossing) and invited us to pitch our tent at the police compound. Another policeman told us that the road onwards would improve and stamped his feet on the hard-packed surface of the police compound, suggesting that that was what we could expect from now on. By now it was 5pm. The sun would set in 90 minutes. We were knackered but decided to press on. It was just 10km to get to our intended destination.

Sadly, the policeman’s description of the road ahead was entirely inaccurate. Once again we were forced to dismount and heave our bikes through the sand.

As the sun went down behind the distant mountain, we were forced to call the day’s ride to an end – just 3km from our target destination. We camped in the bush amidst billions of mosquitos and insects. Later that night, I discovered that the flying sharks had attacked my back by biting straight through my shirt. Emily lost count at over 100 bites. Not great when we’re in a malarial area and aren’t taking prophylactics.

Since leaving Addis Ababa, we’d been on the road for 10 days straight – our longest period without a break. The terrain had been hilly. The kids were horrendous. We had rocks thrown at us several times a day. We’d been munched by mosquitos. The roads had petered out and turned into riverbeds. We’d had to haul our bikes through kilometer after kilometer of sand. The mercury topped 50 degrees on most days. All this had put a huge toll on our bodies and has triggered a few medical issues. We needed a break. We needed a refuge. And we found that just 3km up the road the next morning at the Our Lady Queen of Peace Catholic mission in Todonyang – the first town in Kenya.

We were greeted warmly by Father Andrew, pitched our tent under a tree and brought cold, crisp water by a charming chap named Cosmos. Father Andrew told us that the road between the mission and Lodwar was the same sandy surface we’d suffered.

It would have taken us 7 to 10 days to travel the West Turkana route by bicycle. And we would have had to haul our bikes through the sand and more dried riverbeds. Something we didn’t have the health to do. The next day, we strapped our bikes to the top of the 4×4 and joined Father Andrew (as he drove like a man on a mission) and friends for the incredibly bumpy and uncomfortable trip to Lodwar, where we are now. En route we saw a monument that marks the spot of the oldest skull to have ever been found. Turkana Boy.

We shall make up the miles we missed. In Lodwar, we’ll get ourselves checked out by doctors and speak to the police about the security situation on the road ahead. The long and lonely road between Lodwar and Kitale is renowned for bandits and tribal conflict so we need to get up to date advice on what to expect. Should we need to bypass this section we’ll make those miles up too.

Ethiopia has been an immense challenge that’s left us both utterly exhausted. It’s a beautiful country. But it’s incredibly difficult cycling over such terrain and, despite some magical experiences in the tribal lands of the Omo valley, enduring the constant ‘difficult’ interactions with the people. I’ve found the country has brought out an angry side in us at times. I’ve lost my temper of numerous occasions in situations where I’d normally be mild mannered. When rocks have been thrown at us by children I shamefully admit to returning a few of them with interest. It’s an anger that I’m leaving at the border. And, once we’re fit again, we’re both hugely excited about the journey ahead in Kenya and into Uganda where we expect to be cheered rather than jeered. And where a cold bottle of water is, hopefully, only a village away.